Growing up I remember success being defined in many ways, but one spotlight example was the elusive $100,000 income – or at least the ability to make $100,000 per year. In the 90’s I thought someone was “rich” if they made more than $100,000 a year. Granted I was only a teenager at the time, but the point was… it was the benchmark I used to gauge my success when I graduated college. Today, success looks very different… so much so that American’s making $100,000 per year are defined as the top end of the middle class.

To think 25% to 35% of Americans have made over $100,000 since the mid-90’s it is impressive; and yet to believe purchasing power of that same amount has dropped by 50% is crazy. In other words, $100,000 in 1995 would have needed to increase to over $200,000 today to maintain the same buying power. No wonder more than half of all Americans making $100,000 are living paycheck to paycheck.

However, it is only when we dig deeper that we see what percentage of the 130 million American households make less than $100,000 per year. According to the US Census approximately 63% of American households make $100,000 a year or less. Furthermore, half of those households, or approximately 34% of the total, make less than $50,000. Therefore, if the median income across the United States is approximately $75,000 then how long will it be before $100,000 becomes the lower middle class?

This is where our story begins…

15 Years Of Free Money

When I was just about to graduate high school Y2K was the hot topic running rampant through the streets. People were worried that a simple tick from 1999 to 2000 across the world’s computer systems would bring the world to its knees. While the actual logic behind the change over is a little more complex, the point is simple… the world panicked over what became a fairly trivial issue. We all woke up on January 1st and the world didn’t end. Unfortunately, what ensued in the following years lead to what was coined “the lost decade” making some wish the world had ended at the turn of the century.

The 2000’s were a pretty crazy up and down roller coaster for an entire decade. During the course of 2000’s America experienced the first major market crash since the late 80’s, American’s experienced the worst terrorist attack since the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, between 2003 to 2007 many Americans saw their home prices skyrocket as a result of easy lending standards, and between 2007 and 2009 almost every American was impacted by what was later called the Great Financial Crisis – a byproduct of the loose bank lending standards over the prior years. In fact, the crisis that was frequently compared to the Great Depression of the 1920’s.

As a result of the Great Financial Crisis the Federal Reserve pumped massive amounts of money into the American economy through a process known as Quantitative Easing over the following years. Quantitative Easing allowed banks and corporations to borrow money from the Federal government as a means to stave off systemic problems to the American economy. Unfortunately, the use of quantitative easing led to the explosive growth of the Federal government’s balance sheet (or debt). The act of maintaining loose monetary lending policies and unsustainable fiscal spending essentially moved the private sector’s debt to the public sector in an attempt to prevent a collapse of the American economy.

As a result of the massive stimulus the Federal government’s debt had ballooned so much that in 2011 S&P Global, one of the rating agencies that contributed to the Great Financial Crisis, wrote a report stating the fiscal and monetary path the US government was on was unsustainable. That report led to the recommendation of the first US government debt downgrade in over 100 years. Sadly, the facts outlined in that report were never heeded and the Federal government continued on its spending spree over the following decade with stratospheric sums of money pumped into the American economy.

To help fuel economic growth and keep interest payments (on the staggering sum of US debt) low the Federal Reserve elected to maintain a low interest rate policy from 2009 until 2018. In an attempt to slow the speed of economic growth and pull some of the money, pumped into the American economy, out of the system the Federal Reserve attempted to increase the Fed Funds rates. While a brave attempt, the US equity markets crashed 20% in a matter of three months (Q4 2018) as a rebuke to the Federal Reserve’s attempt to bring order to a lawless system. This ferocious response led the Federal Reserve to abandon the rate hiking cycle. To make matters worse, the Fed Funds rate eventually dropped back down to near 0% in March of 2020 at the height of the COVID pandemic.

So why does this matter and how does this history lesson apply to US households trying to survive today?

Growing up in a world pre-GFC the average household had to balance their spending between daily consumption, entertainment (i.e. eating out and taking vacations), and financing big ticket items (e.g. car or home purchases). While living expenses are not uncommon during any period of time (even with inflation) the last 15 years of free money – or extremely low interest rates – allowed American households to allocate the extra spending away from interest payments and toward entertainment or other expenses. If your income was high enough, say over $100,000, then you were able to save a little as well.

For example, if a family in 2007 purchased a home with an interest rate between 6-7% (after the real estate market run up) they found themselves spending an extra $500 to $1,500 per month on interest payments – depending on the mortgage amount. As someone who purchased their home in 2008 just below $400k with a 6% interest rate, I can tell you I thought I got a great deal. However, over the next couple of years as interest rates plummeted, and after we refinanced a couple of times, I came to realize the amount of excess disposable cash flow that our household was enjoying somehow found it’s way into nicer things. Luxury cars, nicer trips, gadgets, clothes, and more; not as much to savings though. This “new lifestyle” became the norm for many Americans over the following decade.

Fast forward to 2022 – 2023. The Federal Reserve’s fight to kill the inflation monster, that was sparked from the COVID crash, changed the paradigm. The Fed Funds rate started near 0% and rapidly increased to almost 5.5% in less than two years. While these numbers may not appear dire, it’s the proxy interest rates which track with the Fed Funds rate that have begun to wreak havoc on consumers. For example, depending on the lender, banks align the interest rates for different lending products to proxies like the Prime Rate, the SOFR, and the 10 year Treasury. This means auto loans, credit cards, and mortgages experienced major increases.

According to the St. Louise Federal Reserve, commercial banks charged an average of 11.82% on credit cards in August 2014. By February 2020 credit card interest rates increased to an average of 15.09%. Finally, by November 2023 credit card interest rates reached a high of 21.47%. This means it took six years for interest rates to climb approximately 25% but only three years for interest rates to climb another ~50%. Or stated another way, over the course of nearly 10 years credit card interest rates almost doubled (81.6%). Consumer credit card debt climbed right along with rate hikes.

The rate hikes seen in credit cards were also seen in other areas of the financial sector. New 48 & 60 month auto loans increased from approximately 4% to over 8% between 2015 and 2023. Thirty year fixed home loan interest rates jumped from approximately 3% in 2021 to over 6% today.

If $100,000 was once considered by many to be “rich”, that is no longer the feeling today. Rising inflation, high consumer debt, and high interest rates has turned $100,000 a fight for survival.

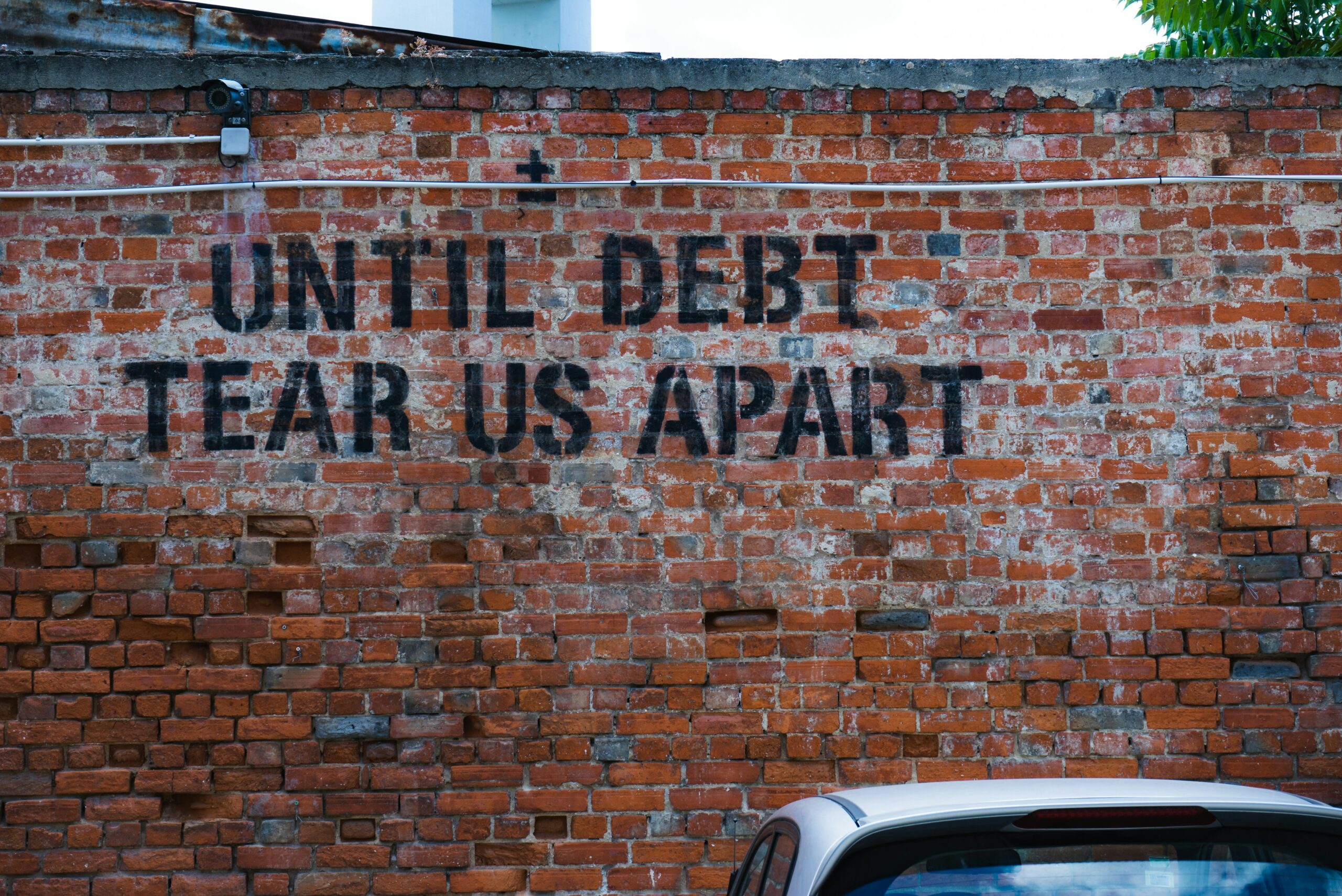

The Mountain Of Debt

Today, the average household is spending almost double the amount they spent three years ago on interest payments alone. If there is a saving grace it’s in the fact that home loans, which represents over 70% of consumer debt, has yet to adjust to higher rates. This is because those who own homes do not want to move and give up their low interest rates. Unfortunately, the lack of selling homes creates a different problem (e.g. home inventory drops, home prices remain high, and rent increases to match spikes in owner equivalent rent).

What makes up the other portion of consumer debt? Well that would consist of student loans, credit cards, auto loans, and other (e.g. personal loans). Representing a little over 30% of consumer debt, these loans carry interest payments that make up more than one-third to one-half of a household’s interest payment on a home.

For example, consider the home I purchased, and later refinanced. My home was purchased for a little less than $400,000 under an FHA program with a 3.5% down payment approximately 15 years ago. Leaving taxes, insurance, and principal out of the equation… the interest payment alone was approximately over $1,850 per month. As rates dropped and equity increased I refinanced to 3% where interest payments are approximately $900 today. This means, with mortgage rates above 6% today, interest payments associated with new home loans will take away from excess spending.

If we look at household credit card debt by age we find that Generation X carries a little more than $8,100, Baby Boomers carry a little more than $6,200, and Millennials carry a little more than $5,500. Assuming these balances carry prevailing credit card interest rates then each group pays approximately $1,700, $1,300, and $1,150 in interest per year, respectively. However, if you add in auto loan debt we find new vehicle debt is approximately $40,000, and used vehicle debt is approximately $27,000. If the average interest rate is 6% then the average monthly interest payment is $200 and $135, respectively.

This means anywhere from $235 to $350 per month is spent on credit card and auto interest payments. For some that may not sound like a lot, but for 34% of America earning less than $50,000 per year, or a net $3,541 per month, this amount of interest represents approximately 10% of monthly income – with no end in sight. Add increased food costs, energy prices, child care expenses, housing costs, student loan payments, along with debt pay down, and consumer interest payments could be the breaking point for one-third (or more) of the American population.

Don’t believe me? Let’s look at the number of consumer delinquencies across all lending products. In Q2 2021 reported delinquencies hit a low of 10,472,000. Fast forward to Q4 2023 and reported delinquencies reached 32,199,000. In a little over two years delinquencies more than tripled. The last time reported delinquencies were this high was in Q2 of 2010 – the wake of the GFC.

To add to the pain, as of Q4 2023 credit card delinquencies reached 9.7%. The last time credit card delinquencies were this high was in Q1 2021 and then in Q2 2013 – the wake of the GFC.

If that wasn’t enough, the recent banking problems experienced within the community and regional banks, as a result of the commercial real estate banking crisis, are showing credit card delinquencies have reached 7.8%… their highest level in over 40 years. As I have explained in other articles, community and regional banks are the key to America’s small business health and expansion. Since many small businesses use credit cards to finance growth, it would be fair to think higher input prices and slower sales are leading to lower growth and more delinquencies. With these regional institutions owning over 40% of the commercial real estate loans and now struggling with consumer credit card delinquencies… the pressure continues to mount. Debt continues to mount.

If consumers spending continues to be fueled by credit, interest payments continue to eat into discretionary spending, and consumers are faced with a mountain of debt then $100,000 could soon become associated with the lower middle class.

Let’s bring this home…

The era of free money is over. Government debt continues to break records every year. Community and regional bank delinquencies are near GFC highs. Charge-offs for the same group was only higher at the peak of the dot.com market crash. Consumers are reaching their breaking point, if not already there. Spending on goods continues to decline. Consumer savings has dropped to multi-year lows. Inflation by all metrics (i.e. CPI, PPI, and PCE) is reaccelerating. Wall Street’s forecast for year-end S&P 500 targets have been met by the end of February.

The setup for a perfect storm is brewing. The number of fuses in both the domestic and international economy are plentiful. The question now becomes, which one gets lite… and when does it all explode?

Content in this material is for general information only and not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. You cannot invest directly in an index. Asset allocation is no guarantee of risk reduction. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.